The Indian Island Candlelight Vigil is held on the last Saturday of February, which this year fell on the actual date of the 1860 massacre on Indian Island: February 26. So when several hundred participants gathered at the west end of Woodley Island, Tribal Chair Cheryl Seidner recalled how the vigil started in 1992, as did two of the other organizers, Marylee Rohde and another woman whose name I heard only as "Ann", though I thought it might be Peggy Betsels.

This was Ann/Peggy's first vigil in ten years, since she had moved away from the area. She said the night before the meeting with Cheryl and Marylee where they would decide what to do to commemorate the Wiyot massacred on Indian Island, she had a "powerful dream" in which she asked for and got the approval of a council of angels.

Just as she was talking about this, people at the vigil began to hear a distant, insistent honking sound, becoming louder. It was the honking of geese, and we looked up to the cloudy sky in the last light to see several long connected lines of geese flying high above us out to the bay. Everyone stopped to watch.

It wasn't the first time that birds had flown in groups over the vigil, but in my experience this was the largest and most vocal presence. It was very impressive. It was impossible not to think of the souls going home to the island.

Especially when Cheryl announced that a deal had been struck with the city of Eureka for 60 more acres of Indian Island. Now that the Wiyot will take possession of almost the entire northern part of Indian Island, Cheryl sounded more hopeful than ever that soon they would be able to invite others to the island for the completion of the ceremonies brutally interrupted 145 years ago, "and the second part of the healing can begin."

During the vigil, Marylee Rohde spoke about how a small group of people "made a difference" when they began the vigils, and how this larger group continues to make a difference. A Native elder whose name I didn't catch reminded everyone that there were other massacres and oppressions in that terrifying time. He said that for example hundreds of Yurok and Tolowa were imprisoned on a small lighthouse island at Crescent City. A Yurok group of fine singers sang Brush Dance songs, which, the leader said, were appropriate because the Bush Dance is a ceremony of healing.

It was a cool night, but not as cold as some have been here. There was only a drop or two of rain, though it seemed to fall only when I had my knitted cap off during Cheryl's prayer.

Someone announced that Cheryl Seidner had been nominated Woman of the Year for District 1. She said that the award was really for everyone who together had accomplished so much. She remembered her parents and others who had come before.

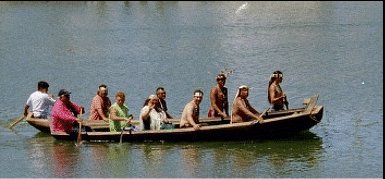

The vigil ended as it has in recent years with Cheryl gathering as many Wiyot as could squeeze into the center of the group and singing with them her Coming Home song. The rest of the assembled took up the song.

I stood near a very old Native couple who were sitting together in two folding chairs, gripping small candles, their heads bowed for most the evening. I couldn't help thinking that their grandparents could have been alive when the last ceremony on Indian Island began, and told them stories of what had happened. The woman's chair was slightly farther ahead of the man's, and at a certain point I saw her reach her hand back to him without looking, and he took it, and they held hands like that for awhile.

Then I watched the speakers and the singers, and when I looked back to where the elders were sitting, they were gone.

The Women of September

-

The first expansion team I remember was the New York Mets. I turned 16

the summer they started playing in 1962. They were terrible. They went

40-120, ...

4 days ago